With ships urged to hurry up, cargo price tens of millions misplaced at sea | Enterprise and Financial system Information

Containers on giant ships carrying everything from car tires to smartphones are falling alarmingly quickly, sinking millions of dollars of cargo to the ocean floor as pressures to expedite deliveries increase the risk of security failures.

The shipping industry has seen its largest increase in lost containers in seven years. More than 3,000 boxes fell into the sea last year, and more than 1,000 boxes have fallen overboard by 2021. The accidents disrupt the supply chains of hundreds of US retailers and manufacturers such as Amazon and Tesla.

There are a variety of reasons for the sudden surge in accidents. The weather is becoming more unpredictable as ships get bigger, allowing containers to be stacked higher than ever before. However, the situation is made significantly worse by a surge in e-commerce after consumer demand exploded during the pandemic, adding to the urgency for shipping lines to get products to be delivered as soon as possible.

“The increased movement of containers means these very large container ships are much closer to full capacity than they have been in the past,” said Clive Reed, founder of Reed Marine Maritime Casualty Management Consultancy. “The ships are under commercial pressure to arrive on time and consequently make more voyages.”

After stormy winds and big waves hit the 364-meter-high One Apus in November and lost more than 1,800 containers, thousands of steel boxes were shown scattered on board like pieces of Lego, some of which had been torn into shreds of metal. The incident was the worst since 2013, when the MOL Comfort broke in two and sank into the Indian Ocean with its entire cargo of 4,293 containers.

In January, Maersk Essen lost about 750 boxes while sailing from Xiamen, China to Los Angeles. A month later, 260 containers fell from Maersk Eindhoven when it lost energy in heavy seas.

The need for speed creates precarious conditions which, according to shipping experts, can quickly lead to disasters. The dangers range from stevedores improperly locking boxes on top of each other to captains not straying from a storm to save fuel and time from exposure to pressure from charterers, they said. One wrong movement can endanger the cargo and the crew.

The likelihood of mishaps increases as exhausted seafarers face deteriorating conditions during the pandemic. Allianz Global Corporate & Specialty estimates that human error contributes to at least three quarters of accidents and deaths in the shipping industry.

Almost all recent incidents have occurred in the Pacific Ocean, a region where the busiest traffic and the worst weather collide. The sea route, which connects the Asian economies with consumers in North America, has been the most lucrative for shipping companies over the past year. China’s exports have faltered as the pandemic fuels crave everything people need to work, study and entertain from home.

The journey has always been difficult, but it has become more dangerous due to changing weather conditions. The surge in traffic from China to the US last winter coincided with the strongest winds over the North Pacific since 1948, increasing the likelihood of rough seas and larger waves, said Todd Crawford, chief meteorologist at The Weather Company.

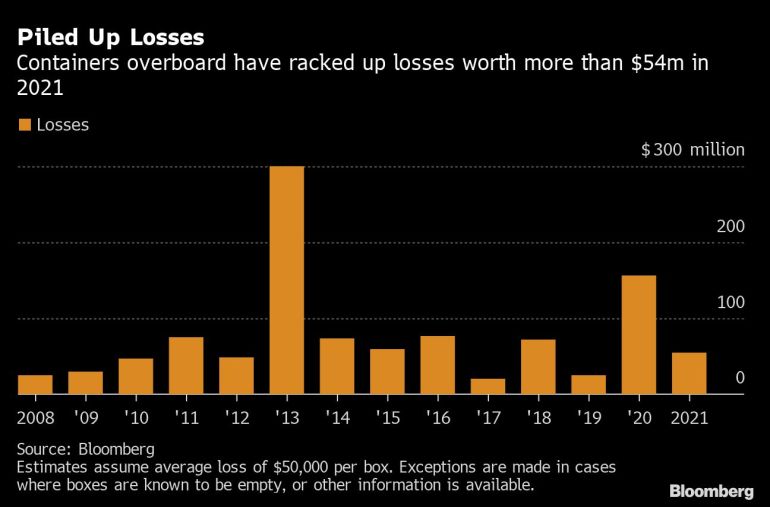

The launch of Ever Given in the Suez Canal last month brought the vulnerability of the shipping industry to the fore. So far this year, freight losses have been nearly $ 55 million [File: Islam Safwat/Bloomberg]With 226 million container boxes a year, losing 1,000 or more can seem like a drop in the ocean. “That’s a very small percentage of the loss,” said Jacob Damgaard, assistant director of loss prevention at Britannia P&I, at a conference in Singapore on April 23rd.

The launch of Ever Given in the Suez Canal last month brought the vulnerability of the shipping industry to the fore. So far this year, freight losses have been nearly $ 55 million [File: Islam Safwat/Bloomberg]With 226 million container boxes a year, losing 1,000 or more can seem like a drop in the ocean. “That’s a very small percentage of the loss,” said Jacob Damgaard, assistant director of loss prevention at Britannia P&I, at a conference in Singapore on April 23rd.

According to Jai Sharma, a partner at law firm Clyde & Co. in London, the One Apus lost $ 90 million in freight alone, averaging $ 50,000 per box. This is the highest value in recent history. According to Bloomberg data, losses so far this year have been estimated at $ 54.5 million.

The issue is also gaining attention when the landing of the 400-meter ship Ever Given in the Suez Canal last month highlighted the vulnerability of the shipping industry. The mega-ship blocked traffic through the vital waterway for almost a week and the effects on world trade are still being felt.

So far, none of the recent container accidents have been directly attributed to security breaches. The International Maritime Organization said it was awaiting the results of the investigation into the recent incidents and warned against drawing any conclusions beforehand.

However, many experts say the situation has become more dangerous because of the pressure on supply chains since the pandemic. When ships approach severe weather, captains have an opportunity to stay away from the danger. But the attitude is, “Don’t go around the storm, go through it,” said Jonathan Ranger, head of Marine Asia Pacific at American International Group Inc.

“When you combine that with potentially poor maintenance of the twistlocks and wiring required to secure these boxes, this is an accident waiting to happen,” he said at the industry conference in Singapore.

Top heavy

If the boxes are stacked higher and higher, a ship can become more unstable in a storm – wave after wave, the ship can roll at steep angles and strain the securing of the containers. The situation gets worse when the stack is top heavy. This can happen if the bills of lading for containers are incorrectly weighted, which many industry representatives believe is too common.

“You can’t see inside the containers,” said Arnaldo B. Romero, a captain who sailed from Japan to South America late last year. “If the cargo is heavy and the cargo planning officer pulls it up while the ship is taxiing, we may be out of control.”

Overworked crews also increase the risks. Less labor on board with an increased number of containers on deck makes it increasingly difficult for crews to effectively check every single rod and screw, said Neil Wiggins, managing director of Independent Vessel Operations Services Ltd.

It is also about the health and safety of seafarers. Overturning multiple levels of 40-foot containers during a raging storm is one of the most terrifying experiences for a captain and crew. According to Philip Eastell, founder of Container Shipping Supporting Seafarers, post-traumatic stress disorder is common among crew members.

The industry’s concern about dealing with the situation is growing.

“Traffic at sea is different from what it was 10 years ago,” said Rajesh Unni, founder of Synergy Marine Group, which provides services to shipowners. “How do we adapt as an industry? It’s easy to blame the captain, but we need to look at how port infrastructure needs to change and how ships pass through. “

The IMO, the United Nations maritime regulation agency, says countries whose flags the ships sail are responsible for issuing safety certificates for ships, while ports the ships call at are responsible for ensuring the rules for the loading of containers must be complied with.

The agency said its subcommittee on moving cargoes routinely deals with container issues and has scheduled its next meeting for September.

According to AIG’s rangers, companies should be prepared to bypass storms and properly maintain ships. “These ships are designed to carry the boxes, and having these losses is – I can only say – unacceptable.”